미토콘드리아에 존재하는 잘못된 DNA를 파괴함으로써 ‘세 부모 배아’에 대한 대안이 될 수 있는 방안을 찾게 되었다.

앞으로 산모는 미토콘드리아에서 유전적인 문제를 아기에게 유전되는 것을 막을 수 있을 것이다. 질병에 걸린 난자를 조작하는 치료는 임상수준에서 사용 가능할 정도로 발전되고 있지만 연구자들은 아직 이 기술에 대한 윤리적인 문제와 안전성에 관한 문제를 둘러싸고 논쟁을 벌이고 있다. 산모의 난자 핵과 건강한 여성의 난자를 결합하여 ‘세 부모 배아’를 만들어내는 것과 연관되고 있다.

학술지 <Cell>지에 발표된 논문에서 한 연구팀은 대안을 제시했다: 잘못된 미토콘드리아를 중립화시키는 방안이다. 일부 연구자들은 이 접근법은 윤리적으로 문제가 되고 있는 조작된 인간배아의 특성이 다음 세대로 전달될 수 있다는 우려 문제를 해결할 수 있다고 보고 있다. 전세계적으로 약 5,000명 중에서 한 명은 에너지를 세포에 공급하는 세포기관인 미토콘드리아가 잘못되는 경우에 일어나는 질병을 앓고 있다. 다른 경우에 이 잘못된 세포기관은 암과 같은 다른 질병을 악화시킬 수 있다. 약 60~95%의 미토콘드리아는 질병으로 발전될 수 있을 만큼 잘못되어 있다. 하지만 대부분의 경우에 한 개의 난자에 수천 개의 미토콘드리아의 극히 일부가 잘못될 수 있다고 이번 연구의 저자인 캘리포니아 라홀라 (La Jolla)의 설크 생물과학연구소 (Salk Institute for Biological Studies)의 알레한드로 오캄포 (Alejandron Ocampso)는 말했다.

설크 연구소의 다른 발달생물학자인 후안 카를로스 이즈피수아 벨몬테 (Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte)와 오캄포는 난자 또는 수정된 배아에서 돌연변이를 일으키는 미토콘드리아의 양을 줄이게 되면 질병으로 발달할 수 있는 가능성도 줄일 수 있다는 사실을 발견했다. 이들은 핵산중간분해효소 (endonuclease)라고 불리는 DNA를 잘라내는 효소를 생산하도록 만들어진 RNA파편을 세포에 주입하였다. 이 핵산중간분해세포는 특정한 돌연변이를 갖고 있는 미토콘드리아를 찾아서 그 DNA를 파괴한다.

오캄보와 이즈피수아 벨몬테는 실험쥐 난자와 각기 다른 실험쥐 계통의 미토콘드리아 DNA를 가지고 있는 단세포 배아를 대상으로 실험했다. 이들은 한 계통의 DNA를 제거한 핵산중간분해효소를 만들도록 디자인된 RNA를 세포에 주입했으며 이렇게 만들어진 배아를 대리모에 이식했다. 테스트를 통해서 표적 계통의 미토콘드리아의 60%가 파괴되었으며 아기 실험쥐는 건강했다. 두 번째 실험에서 연구자들은 미토콘드리아 질환을 앓고 있는 사람의 미토콘드리아를 실험쥐의 난자와 결합하였다. 이들 세포에서 맞춤형 RNA는 손상된 미토콘드리아의 20~50% 정도를 제거했다.

이 기술을 임상적으로 사용하기에는 아직 너무 이른 단계이다. 인간의 생식세포주와 배아를 편집하는 것은 많은 국가에서 불법이며 비윤리적이라고 비난을 받고 있다. 최근 몇몇 연구자들은 법적으로 받아들일 수 있는 연구 또는 임상적인 적용을 위한 가이드라인이 개발될 때까지 연구 모라토리엄이 필요하다고 주장하고 있다. 이즈피수아 벨몬테와 오캄보는 이 기술을 인간세포에 적용하기 전까지 윤리위원회의 허가를 기다리고 있다고 밝혔다.

연구자들은 아직도 이번 접근법을 증진시켜야 할 필요가 있으며 배아에 손상이 없도록 해야 한다고 영국 캠브리지 대학의 분자생물학자인 미칼 민주크 (Michal Minczuk)는 말했다. 배아의 미토콘드리아 DNA의 상당부분을 파괴하는 것은 배아가 자궁에 착상되기 어렵게 만든다고 그는 말했다. 그리고 캐나다의 맥길 대학 (McGill University)의 분자생물학자인 에릭 슈브리지 (Eric Shoubridge)는 개별 환자를 위한 RNA를 공학적으로 조작하는 것은 미토콘드리아 질병을 일으키는 많은 돌연변이로 인해 어렵다고 밝혔다.

이번 접근법은 난자 사이의 핵과 미토콘드리아를 전환시키는 ‘세 부모 배아’의 필요성을 제거할 수 있다. 이것은 세포를 손상시킬 수 있으며 전체적인 개념상 많은 과학자들과 법을 만드는 사람들에게 문제를 일으켰다. 반면에 맞춤형 RNA를 주입하는 것은 “어떤 불임클리닉에서도 실행할 수 있는 방법”이라고 이즈피수아 벨몬테는 말했다. 캘리포니아주의 버클리에 위치한 유전학과 사회 연구센터 (Center for Genetics and Society)의 디렉터인 마시 다노프스키 (Marcy Darnovsky)는 이 접근법은 또한 세 부모 배아의 개념으로 제기된 문제를 피할 수 있을 것이라고 말했다. 하지만 그녀는 이 방법이 임상에 곧 사용될 것이라는 주장에 대해서 회의적이다. 그 이유는 건강한 아이는 질병을 치료하는 것과 동일하지 않기 때문이며 그래서 위험을 넘어설 수 있다. 그리고 가장 엄격하게 미토콘드리아 편집이 생식세포주의 조작을 일으킬 수 있다고 말했다.

슈브리지는 “이것은 마치 가파른 절벽과 같다. 만일 어떤 편집 기술을 허락하게 된다면 이것은 무엇이든 편집할 수 있는 판도라 상자를 여는 것과 같다. 우리가 주목하는 것은 윤리적인 문제이다. 어떻게 해야 할지 잘 모르겠다”고 말했다. 과학적인 장애물도 또한 남아있다. 영국 뉴캐슬 대학 (Newcastle University)의 신경학자이며 핵을 건강한 난자제공자에게 이식하는 기술을 개발한 더글러스 턴불 (Douglas Turnbull)은 이번 실험쥐를 대상으로 한 연구는 매우 고도의 흥미로운 결과라고 말했다. 하지만 잘못된 미토콘드리아가 많은 여성의 난자는 적중과정에서 살아남지 못한다. 그 이유는 세포기관의 DNA가 너무 적기 때문이다. 그럼에도 불구하고 오캄포와 이즈피수아 벨몬테는 버려진 인간난자와 난자를 처리할 수 있는 허가를 기다리고 있으며 윤리위원회의 허가를 기다리고 있다고 밝혔다. 이들은 이 조작된 세포에서 줄기세포주를 개발할 계획이지만 이 배아를 산모에게 착상시키지는 않을 것이라고 밝혔다.

출처: <네이처> 2015년 4월 26일 (Nature doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17379)

원문참조:

Reddy, P. et al. Cell http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.051 (2015).

Liang, P. et al. Protein Cell http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5 (2015).

Russell, O. & Turnbull, D. Exp. Cell Res. 325, 38–43 (2014).

Lanphier, E. et al. Nature 519, 410–411 (2015).

Baltimore, D. et al. Science 348, 36–38 (2015).

http://www.nature.com/news/dna-editing-in-mouse-embryos-prevents-disease-1.17379

DNA editing in mouse embryos prevents disease

Destroying faulty DNA in mitochondria could be alternative to ‘three-parent embryo’.

Sara Reardon 23 April 2015

Article toolsRights & Permissions

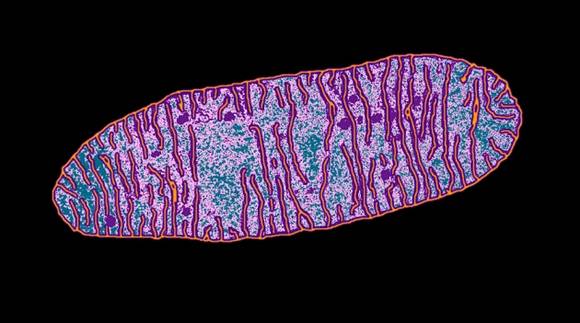

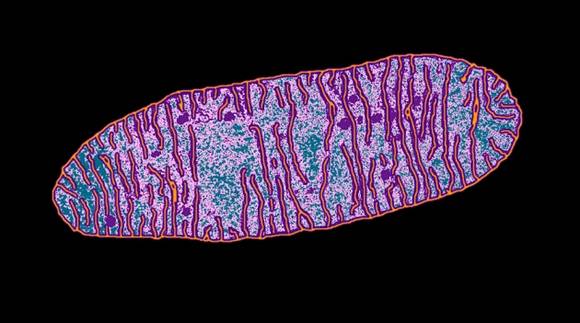

Dr. Don Fawcett/Getty

A typical egg carries hudnreds of thousands of mitochondria, such as the one shown here.

Mothers may one day be able to prevent their children from inheriting mitochondrial defects. Therapies that modify diseased eggs are inching closer to the clinic, but researchers are still hotly debating the safety and ethics of the most promising techniques. These involve combining the nucleus of the mother’s egg with mitochondria from a healthy woman to create a ‘three-parent embryo’.

In the 23 April issue of Cell1, one team proposes an alternative: neutralizing the faulty mitochondria. Some researchers say that the approach could help enable the ethically questionable practice of engineering human embryos to have modifications that would be passed on to future generations. (The first instance of such engineering was published in Protein & Cell2 and reported by Nature's news team on 22 April.)

About 1 in 5,000 people worldwide has a disorder caused by faulty mitochondria, the organelles that supply the cell with energy. In others, the faulty organelles worsen diseases that arise by other means, such as some cancers. Roughly 60–95% of the mitochondria in a cell must be faulty for disease to develop3. In most cases, however, just a small fraction of the hundreds of the thousands of mitochondria in an egg carry flaws, says Alejandro Ocampo, a molecular biologist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, and an author of the Cell study.

Related stories

•Chinese scientists genetically modify human embryos

•Don’t edit the human germ line

•Scientists cheer vote to allow three-person embryos

More related stories

Ocampo and Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a developmental biologist at Salk, realized that reducing the amount of mutant mitochondrial DNA in an egg or fertilized embryo could reduce the chance of disease developing. They did this by injecting the cells with a segment of RNA that was designed to produce a DNA-cutting enzyme known as an endonuclease. The endonuclease would then seek out mitochondria with a specific mutation and destroy their DNA by snipping it.

Ocampo and Izpisua Belmonte ran their experiment on mouse eggs and one-cell embryos that contained mitochondria with DNA from two different mouse strains. They injected the cells with RNA designed to create endonucleases that knock out DNA from just one strain, and implanted the embryos into surrogate mothers. Tests revealed that around 60% of the mitochondrial DNA from the targeted strain had been destroyed — and the resulting baby mice were healthy.

In a second experiment, the researchers fused mouse eggs with mitochondria from people with mitochondrial diseases; in these cells, the customized RNA eliminated 20–50% of damaged mitochondrial DNA.

Early results

The technique is still far from being available to parents. Editing human germ cells and embryos is illegal in many countries and is widely considered unethical4, 5. In recent weeks, several research groups have called for a moratorium on such work until guidelines can be developed to delineate legally and ethically acceptable research or clinical applications. Izpisua Belmonte and Ocampo are waiting for approval from ethics boards before applying their technique to human cells.

Even then, the researchers would still need to prove that their approach does not damage the embryo, says molecular biologist Michal Minczuk of the University of Cambridge, UK. Destroying a large proportion of an embryo’s mitochondrial DNA could make it difficult for the embryo to implant in the uterus, he says.

And molecular geneticist Eric Shoubridge of McGill University in Montreal, Canada, says that it could be difficult to engineer RNA for individual patients, because there are so many mutations that cause mitochondrial disease.

The approach could eliminate the need for ‘three-parent embryo’ techniques, which involve moving nuclei or mitochondria between eggs. This can damage the cells, and the overall concept has given many scientists and lawmakers pause. By contrast, injecting customized RNA “is something that any IVF clinic can do with their eyes closed”, Izpisua Belmonte says.

Marcy Darnovsky, director of the Center for Genetics and Society in Berkeley, California, says that the approach would also avoid many of the concerns posed by the concept of three-parent embryos, which her group opposes. But she remains sceptical that these methods will make it into the clinic any time soon, as creating a healthy child is not the same as curing a disease — and therefore may be outweighed by the risks. And in the strictest sense, she adds, mitochondrial editing still creates modifications in the germline.

“It is a bit of a slippery slope — if you start allowing any editing tool, you open a Pandora’s box of the possibility to edit anything,” says Shoubridge. “Whether we want to go down that road is an ethical question. I'm not sure we do.”

Scientific hurdles might also remain. Douglas Turnbull, a neurologist at Newcastle University, UK, who pioneered the transfer of nuclei into healthy donor eggs, says that the mouse work is elegant and exciting. But he notes that eggs from women with high numbers of faulty mitochondria may not survive the knockout process, because so little of the organelles' DNA would remain.

Nevertheless, Ocampo and Izpisua Belmonte say that they are in the process of acquiring discarded human eggs and embryos from a fertility clinic, and waiting for approval from an ethics board. They plan to develop a line of stem cells from these modified cells, but say that they will not implant embryos into mothers or allow them to grow.

Journal name: Nature

DOI: doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17379