21세 때 총상을 입고 나서 목 아래로 마비가 된 에릭 소르토(Erik G. Sorto)는 이제 단지 로봇 팔을 생각하고 자신의 상상력만으로 이 로봇 팔을 움직일 수 있다.

이러한 성과는 미국의 캘리포니아 공대(Caltech), 서던 캘리포니아 대(USC: University of Southern California)의 켁크 의대(Keck Medicine), 란쵸 로스 아미고스 국립 재활 센터(Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center) 등의 연구자들이 임상적 협업을 통하여 달성되었다. 이제 34세인 에릭 소르토는 팔을 움직이고자 하는 의도를 생성하는 기능을 가진 뇌 영역에 이식된 신경 보철 장치를 가지는 세계 최초의 인간이다.

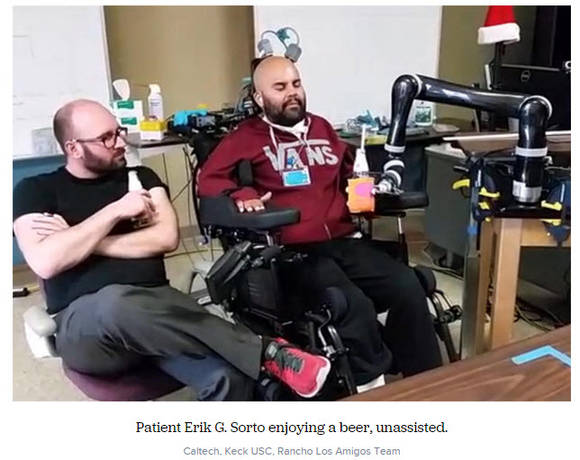

이러한 신경 보철 장치의 이식을 통하여 에릭 소르토는 로봇 팔을 이용하여 부드러운 손 흔들기 동작을 수행하거나, 음료수를 마시거나, 심지어 로봇 팔로 가위 바위 보 놀이를 수행할 수 있다.

기존의 신경 보철 장치는 뇌에서 운동을 관장하는 운동 피질(motor cortex: 대뇌 반구에서 중심구 앞쪽에 있는 신피질 영역으로 수의적 근육 운동을 통제함.)에 이식되어 마비 환자가 로봇 팔의 동작을 제어할 수 있게 한다. 그러나 운동 피질에 이식된 기존의 신경 보철 장치가 만드는 동작은 지연이 있고 덜컥거린다. 그래서 기존의 신경 보철 장치로는 자연스러운 동작과 연관되는 부드럽고 겉보기에 자동으로 수행되는 몸짓을 달성하지 못했다.

이제 캘리포니아 공대 연구자들은 신경 보철 장치를 직접적으로 동작을 제어하는 뇌의 운동 피질이 아닌 움직이려는 의도를 제어하는 뇌의 다른 부분에 이식하여 좀 더 자연스럽고 부드러운 동작을 만드는 방법을 개발하였다.

이 새로운 접근법이 가지는 안전성과 유효성을 시험하기 위하여 캘리포니아 공대의 신경과학 교수인 리차드 안데르센(Richard Andersen), 서던 캘리포니아 대의 신경외과, 신경학 및 의용 생체공학 교수이자 신경과 의사인 찰스 리우(Charles Y. Liu), 란쵸 로스 아미고스 국립 재활 센터의 최고 의료 책임자이자 신경학자인 민디 아이센(Mindy Aisen) 등은 협력하여 임상 시험을 수행하였다.

리차드 안데르센과 그의 동료 연구자들은 뇌의 운동 피질이 아닌 뇌의 다른 영역에서 신호를 수집하여 신경 보철 장치가 환자에게 제공할 수 있는 동작의 다재다능함을 개선할 수 있기를 원하였다. 뇌의 다른 영역은 다름이 아닌 후방 두정엽(PPC: posterior parietal cortex)으로 높은 수준의 인지를 담당하는 영역이다.

리차드 안데르센 교수 연구팀은 이전에 수행한 동물 연구에서 동작을 만드는 초기 의도가 형성되는 곳이 후방 두정엽(PPC)이라는 것을 발견하였다. 다음으로 이러한 의도는 운동 피질로 전달되며, 척수(spinal cord)를 통하여 실제 동작이 수행되는 팔과 다리로 전달된다. "후방 두정엽(PPC)은 이러한 신호 전달 경로에서 좀 더 앞서있다. 따라서 이곳의 신호는 운동 실행에 대한 상세한 내용보다는 당신이 실제로 무엇을 의도하였는가와 같은 운동 계획(motion planning)과 좀 더 연관되어 있다”고 리차드 안데르센 교수가 말했다.

“당신은 팔을 움직일 때 실제로 어떠한 근육을 활성화할지에 대하여 생각하지 않는다. 예를 들어 당신이 컵을 잡는 경우 팔 올리기, 팔 내밀기, 컵 잡기, 컵 주위를 손으로 감싸기 등과 같은 세세한 동작을 생각하지 않는다. 대신에 당신은 예를 들어 ‘나는 물이 담긴 저 컵을 잡고 싶다’ 등과 같이 동작의 목표를 생각한다. 그래서 우리는 임상 시험에서 피험자에게 수많은 요소들로 분해하는 대신에 단순히 전체적으로 동작을 상상하라고 요구함으로써 실제 의도를 성공적으로 해독할 수 있었다. 후방 두정엽(PPC)에서 오는 신호가 환자들이 사용하기에 더 쉽고, 궁극적으로 동작 절차를 좀 더 부드럽게 만들 것으로 우리는 기대한다”고 리차드 안데르센 교수가 설명하였다.

리차드 안데르센 교수 연구팀이 개발한 장치는 서던 캘리포니아 대(USC: University of Southern California)의 켁크 병원(Keck Hospital)에서 2013년 4월에 에릭 소르토에게 외과적으로 이식되었다. 에릭 소르토는 이식된 이후로 마음으로 컴퓨터의 커서(cursor)와 로봇 팔을 제어하기 위하여 캘리포니아 공대의 연구자와 란쵸 로스 아미고스 국립 재활 센터의 직원들과 함께 훈련을 수행해오고 있다. 마침내 연구자들은 로봇 팔의 직관적 운동이라는 자신들의 희망을 목격하게 되었다.

아이가 둘 있는 홀아비이며, 지난 10년 동안 마비된 상태로 살고 있는 에릭 소르토는 빠른 결과에 아주 흥분했다. “나는 로봇 팔을 제어하는 것이 얼마나 쉬운지를 깨닫고 놀랐다. 나는 이 순간을 마치 유체이탈을 경험한 것처럼 기억한다. 그리고 나는 주위를 막 돌아다니면서 모든 사람들과 기쁨의 표시로 서로 손바닥을 마주치는 하이파이브를 하고 싶었다”고 에릭 소르토가 말했다.

[관련 동영상의 연결]

[관련 논문의 연결]

Tyson Aflalo, Spencer Kellis, Christian Klaes, Brian Lee, Ying Shi, Kelsie Pejsa, Kathleen Shanfield, Stephanie Hayes-Jackson, Mindy Aisen, Christi Heck, Charles Liu, Richard A. Andersen. Decoding motor imagery from the posterior parietal cortex of a tetraplegic human. Science, 2015 DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa5417

Intuitive control of robotic arm using thoughts alone

Date: May 21, 2015

Source: University of Southern California - Health Sciences

Summary: Through a clinical collaboration between Caltech, Keck Medicine of USC and Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, a 34-year-old paralyzed man is the first person in the world to have a neural prosthetic device implanted in a region of the brain where intentions are made, giving him the ability to perform a fluid hand-shaking gesture, drink a beverage, and even play 'rock, paper, scissors,' using a robotic arm.

Paralyzed from the neck down after suffering a gunshot wound when he was 21, Erik G. Sorto now can move a robotic arm just by thinking about it and using his imagination.

Through a clinical collaboration between Caltech, Keck Medicine of USC and Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, the now 34-year-old Sorto is the first person in the world to have a neural prosthetic device implanted in a region of the brain where intentions are made, giving him the ability to perform a fluid hand-shaking gesture, drink a beverage, and even play "rock, paper, scissors," using a robotic arm.

Neural prosthetic devices implanted in the brain's movement center, the motor cortex, can allow patients with paralysis to control the movement of a robotic limb. However, current neuroprosthetics produce motion that is delayed and jerky--not the smooth and seemingly automatic gestures associated with natural movement. Now, by implanting neuroprosthetics in a part of the brain that controls not the movement directly but rather our intent to move, Caltech researchers have developed a way to produce more natural and fluid motions.

Designed to test the safety and effectiveness of this new approach, the clinical trial was led by principal investigator Richard Andersen, the James G. Boswell Professor of Neuroscience at Caltech, neurosurgeon Charles Y. Liu, professor of neurological surgery, neurology, and biomedical engineering at USC, and neurologist Mindy Aisen, chief medical officer at Rancho Los Amigos.

Andersen and his colleagues wanted to improve the versatility of movement that a neuroprosthetic can offer to patients by recording signals from a different brain region other than the motor cortex, i.e., the posterior parietal cortex (PPC), a high-level cognitive area. In earlier animal studies, the Andersen lab found that it is here, in the PPC, that the initial intent to make a movement is formed. These intentions are then transmitted to the motor cortex, through the spinal cord, and on to the arms and legs where the movement is executed.

"The PPC is earlier in the pathway, so signals there are more related to movement planning--what you actually intend to do--rather than the details of the movement execution," Andersen says. "When you move your arm, you really don't think about which muscles to activate and the details of the movement--such as lift the arm, extend the arm, grasp the cup, close the hand around the cup, and so on. Instead, you think about the goal of the movement, for example, 'I want to pick up that cup of water.' So in this trial, we were successfully able to decode these actual intents, by asking the subject to simply imagine the movement as a whole, rather than breaking it down into a myriad of components. We expected that the signals from the PPC would be easier for patients to use, ultimately making the movement process more fluid."

The device was surgically implanted in Sorto's brain at Keck Hospital of USC in April 2013, and he since has been training with Caltech researchers and staff at Rancho Los Amigos to control a computer cursor and a robotic arm with his mind. The researchers saw just what they were hoping for: intuitive movement of the robotic arm.

Sorto, a single father of two who has been paralyzed for over 10 years, was thrilled with the quick results: "I was surprised at how easy it was [to control the robotic arm]," he says. "I remember just having this out-of-body experience, and I wanted to just run around and high-five everybody."

The Surgery

The surgical team at Keck Medicine of USC performed the unprecedented neuroprosthetic implant in a five-hour surgery on April 17, 2013. Liu and his team implanted a pair of small electrode arrays in two parts of the posterior parietal cortex, one that controls reach and another that controls grasp. Each 4-by-4 millimeter array contains 96 active electrodes that, in turn, each record the activity of single neurons in the PPC. The arrays are connected by a cable to a system of computers that process the signals, to decode the brain's intent and control output devices, such as a computer cursor and a robotic arm.

"These arrays are very small so their placement has to be exceptionally precise, and it took a tremendous amount of planning, working with the Caltech team to make sure we got it right," says Liu, who also is director of the USC Neurorestoration Center and associate chief medical officer at Rancho Los Amigos. "Because it was the first time anyone had implanted this part of the human brain, everything about the surgery was different: the location, the positioning and how you manage the hardware. Keep in mind that what we're able to do--the ability to record the brain's signals and decode them to eventually move the robotic arm--is critically dependent on the functionality of these arrays, which is determined largely at the time of surgery."

The USC Neurorestoration Center's primary mission is to leverage partnerships to create unique opportunities to translate scientific discoveries into effective therapies.

"We are at a point in human research where we are making huge strides in overcoming a lot of neurologic disease," says neurologist Christianne Heck, associate professor of neurology at USC and co-director of the USC Neurorestoration Center. "These very important early clinical trials could provide hope for patients with all sorts of neurologic problems that involve paralysis such as stroke, brain injury, ALS and even multiple sclerosis."

The Rehabilitation

Sixteen days after his implant surgery, Sorto began his training sessions at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, where a computer was attached directly to the ports extending from his skull, to communicate with his brain. The rehabilitation team of occupational therapists who specialize in helping patients adapt to loss of function in their upper limbs and "redesign" the way patients do tasks with the function they have left, worked with Sorto and the Caltech team daily to help Sorto visualize what it would be like to move his arm again.

"It was a big surprise that the patient was able to control the limb on day one¬¬¬--the very first day he tried," Andersen says. "This attests to how intuitive the control is when using PPC activity."

Although he was able to immediately move the robot arm with his thoughts, after weeks of imagining, Sorto refined his control of the arm. Now, Sorto is able to execute advanced tasks with his mind, such as controlling a computer cursor; drinking a beverage; making a hand-shaking gesture; and performing various tasks with the robotic arm.

Aisen, the chief medical officer at Rancho Los Amigos who led the study's rehabilitation team, says that advancements in prosthetics like these hold promise for the future of patient rehabilitation.

"We at Rancho are dedicated to advancing rehabilitation and to restoration of neurologic function through new technologies, which can be assistive or can promote recovery by capitalizing on the innate plasticity of the human nervous system," says Aisen, also a clinical professor of neurology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. "This research is relevant to the role of robotics and brain-machine interfaces as assistive devices, but also speaks to the ability of the brain to learn to function in new ways. We have created a unique environment that can seamlessly bring together rehabilitation, medicine, and science as exemplified in this study."

Sorto has signed on to continue working on the project for a third year. He says the study has inspired him to continue his education and pursue a master's degree in social work.

"This study has been very meaningful to me," says Sorto. "As much as the project needed me, I needed the project. It gives me great pleasure to be part of the solution for improving paralyzed patients' lives. I joke around with the guys that I want to be able to drink my own beer--to be able to take a drink at my own pace, when I want to take a sip out of my beer and to not have to ask somebody to give it to me. I really miss that independence. I think that if it were safe enough, I would really enjoy grooming myself--shaving, brushing my own teeth. That would be fantastic."

"The better understanding of the PPC will help the researchers improve the neuroprosthetic devices of the future," Andersen says. "What we have here is a unique window into the workings of a complex high-level brain area, as we work collaboratively with our subjects to perfect their skill in controlling external devices."