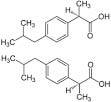

혈액 속에서 용해된 이부프로펜은 두통을 완화시킬 수 있다. 그러나 이부프로펜의 문제는 자연적인 상태에서 부분적으로는 용해되지 않는다는 것이다. 이부프로펜 그 자체로는 고체이고 결정 구조를 띠고 있다. 분자 구조는 군대 대열처럼 길게 연결되어 혈액 속에 잘 녹지 않는다. 이러한 문제를 극복하여 이부프로펜의 용해도를 높이기 위해서 특별한 화학물를 비롯하여 여러 가지 약물을 첨가한다. 그러나 이러한 첨가물은 비용을 증가시키고 또한 약물의 복잡성을 증가시킨다.

이부프로펜과 같은 불용성 약물을 잘 녹이기 위해서는 분자가 군대식 배열을 이루어 결정 구조를 이루는 시간을 주지 않고 비정질 구조체를 이루게 하는 것이 주요한 방법이 될 수 있다.

이번에 하버드 SEAS(Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science) Harvard John A 교수 연구진은 많은 양이 빠르게 용해되는 비정질의 안정된 나노입자를 만들 수 있는 새로운 시스템을 설계하는데 중요하다. 이번 기술은 여러 비정질 나노입자를 만드는데 적용될 수 있다.

이번에 개발된 방법은 단순히 많은 양의 약물을 빠른 시간 내에 녹게 하는데 그치지 않고 비정질 나노입자를 비롯하여 다양한 물질에 적용이 가능한 효과적인 방법이다. 이러한 구조화되지 않은 무기 나노입자는 경정화된 입자와 다른 전기적, 자기적, 광학적 특성을 가지고 있다. 이러한 특성은 재료과학에서부터 광학 분야에까지 다양한 분야에 활용될 수 있는 잠재적인 특성이다.

“이번 결과는 매우 놀랍다. 어떠한 물질도 비정질 나노입자 상태로 만들 수 있다는 것은 엄청난 발견”이라고 이번 연구에 참여한 하버드대학 A. Weitz 교수는 말했다.

이번 기술은 특히 물이나 알코올과 같은 일반적인 용매에 적용이 가능하다는 장점을 가지고 있다. 물이나 알코올에 먼저 용해시킨 후 매우 가는 채널을 통해서 액체 방울을 스프레이 방식으로 공중에 압축 분사시킨다. 이러한 방울은 스프레이 된 후에 수 초 안에 완전히 건조되어 최종적으로 비정질의 나노입자가 된다.

나노입자의 비정질 구조는 완전히 복잡한 구조이다. 분무기와 같은 시스템에서 초음속으로 뿜어져 나오는 방울은 기대했던 것보다 훨씬 빠른 속도로 건조되었다고 연구진은 설명했다. 이는 물에 젖은 몸으로 바람 부는 곳에 서있을 때에 몸이 더 빨리 마르는 것과 같다 바람이 액체를 더 빨리 증발시킨다. 이번 시스템은 이와 유사한 원리라고 연구진은 설명했다. 이러한 빠른 증발은 또한 냉각 속도를 가속시킨다. 땀의 증발이 몸을 더 빨리 식히는 것과 같다. 빠른 증발은 냉각 속도를 가속화시키고 분자들의 움직임을 느리게 한다. 이는 결국 결정의 형성을 막는 역할을 한다고 연구진은 설명했다.

이러한 실험결과는 나노입자의 결정화 억제라는 새로운 방법을 보여주고 있다. 비정질 나노입자는 실온에서 수 개월 동안 매우 안정된 상태로 존재할 수 있다. 이는 기존의 결정질 나노입자와는 매우 다른 특성이다. 연구진은 향후 비정질 무기 나노입자의 특성에 대한 연구와 이를 활용하는 연구를 진행할 계획이라고 밝혔다. 또한 이번 시스템은 조정, 구조, 크기 등 나노입자의 여러 특성을 조절하는 새로운 방법을 제시고 있으며 이는 새로운 물질의 개발 및 설계에 새로운 영감을 불어넣은 계기가 될 것이라고 밝혔다. 이번 연구는 저널 science에 "Production of amorphous nanoparticles by supersonic spray-drying with a microfluidic nebulator"라는 제목으로 게재되었다. (doi/10.1126/science.aac9582

New technique to make drugs more soluble: System makes amorphous particles out of almost anything

August 27, 2015

Before Ibuprofen can relieve your headache, it has to dissolve in your bloodstream. The problem is Ibuprofen, in its native form, isn't particularly soluble. Its rigid, crystalline structures—the molecules are lined up like soldiers at roll call—make it hard to dissolve in the bloodstream. To overcome this, manufacturers use chemical additives to increase the solubility of Ibuprofen and many other drugs, but those additives also increase cost and complexity.

The key to making drugs by themselves more soluble is not to give the molecular soldiers time to fall in to their crystalline structures, making the particle unstructured or amorphous.

Researchers from Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS) have developed a new system that can produce stable, amorphous nanoparticles in large quantities that dissolve quickly.

But that's not all. The system is so effective that it can produce amorphous nanoparticles from a wide range of materials, including for the first time, inorganic materials with a high propensity towards crystallization, such as table salt.

These unstructured, inorganic nanoparticles have different electronic, magnetic and optical properties from their crystalized counterparts, which could lead to applications in fields ranging from materials engineering to optics.

David A. Weitz, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics and Applied Physics and an associate faculty member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, describes the research in a paper published today in Science.

"This is a surprisingly simple way to make amorphous nanoparticles from almost any material," said Weitz. "It should allow us to quickly and easily explore the properties of these materials. In addition, it may provide a simple means to make many drugs much more useable."

The technique involves first dissolving the substances in good solvents, such as water or alcohol. The liquid is then pumped into a nebulizer, where compressed air moving twice the speed of sound sprays the liquid droplets out through very narrow channels. It's like a spray can on steroids. The droplets are completely dried between one to three microseconds from the time they are sprayed, leaving behind the amorphous nanoparticle.

At first, the amorphous structure of the nanoparticles was perplexing, said Esther Amstad, a former postdoctoral fellow in Weitz' lab and current assistant professor at EPFL in Switzerland. Amstad is the paper's first author. Then, the team realized that the nebulizer's supersonic speed was making the droplets evaporate much faster than expected.

"If you're wet, the water is going to evaporate faster when you stand in the wind," said Amstad. "The stronger the wind, the faster the liquid will evaporate. A similar principle is at work here. This fast evaporation rate also leads to accelerated cooling. Just like the evaporation of sweat cools the body, here the very high rate of evaporation causes the temperature to decrease very rapidly, which in turn slows down the movement of the molecules, delaying the formation of crystals."

These factors prevent crystallization in nanoparticles, even in materials that are highly prone to crystallization, such as table salt. The amorphous nanoparticles are exceptionally stable against crystallization, lasting at least seven months at room temperature.

The next step, Amstad said, is to characterize the properties of these new inorganic amorphous nanoparticles and explore potential applications.

"This system offers exceptionally good control over the composition, structure, and size of particles, enabling the formation of new materials," said Amstad. " It allows us to see and manipulate the very early stages of crystallization of materials with high spatial and temporal resolution, the lack of which had prevented the in-depth study of some of the most prevalent inorganic biomaterials. This systems opens the door to understanding and creating new materials."

Explore further: Engineers Produce 'How-To' Guide for Controlling the Structure of Nanoparticles

More information: "Production of amorphous nanoparticles by supersonic spray-drying with a microfluidic nebulator" www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.aac9582

Journal reference: Science

Provided by: Harvard University